If it is a jumble and a junk shop, it nevertheless registers a concept

Ez, referring to the Tempio Malatestiano

Marseille, Marseilles, is not visited by Pound. Instead, I include it out of a personal prejudice in its favour, Oran in 1948. Large parts of the town are heavily dilapidated and it is surely not much more than a third French1; nonetheless it is difficult to tell exactly since the extensive northern slums have seen continual population decline in favour of the rest of the city. The area around the old port, the south of the city, and the western portion beyond the tinkers’ market are excellent, far better than Lyon. People always praise Bordeaux (even those who can’t afford it, by pretending it’s boring), but I have never been and couldn’t comment.

Along with Briançon, Marseille is one of the few French cities founded in a suitable location, and with persistent wind and sea-coast she is always a relief from the actively hostile climate of the lower Rhone valley, whether summer or winter. This vague air of freedom continues to the city’s mostly benign lawlessness2, Marseille probably the only large French city that escapes the demon of control. One of the old hospitals contains a little poetry museum; there is an amusing local tradition they were evangelised by Mary Magdalen, and the procession in her honour was eventually stopped by the Parisian authorities in the 18ᵗʰ century following accusations of license. They had a hymn for the occasion:

Allegron si los pecadors

Lauzan Santa Maria

Magdalena devotament

Ella conoc la sieu’error

Lo mal que fach avia,

Et ac del fuec d’enfer paor

Et mes si en la via

Per que venguet a salvament

Allegron si los peccador

Lauzan Santa Maria

Magdalena devotament

The sinners are rejoicing

Praising St. Mary

Magdalen with devotion.

She knows her sins,

The evil she has worked

And through the fear of hell

She put herself on the way

That leads to salvation

The sinners are rejoicing

Praising Saint Mary

Magdalen with devotion.

And so on. Marseille, a Greek city, had its position stolen in Roman times and was eclipsed by Arles and much later Avignon. The story goes that Arles sided with Caesar and Marseille with Pompey, Arles benefitting from a retirement camp for legionnaires in return (a similar event led to the resettling of Béziers), while Marseille went into a long decline. After the corruption of empire, that is to say the dark ages – there is no such thing as ‘late antiquity’ – the situation is neatly reversed, and Arles lost the majority of its population while Marseille thrived as a trading port, linked to Genoa in some way, which I forget.

A major power in the Middle Ages, not as significant as Genoa (possibly even Narbonne), the city was constrained to the Panier and immediate vicinity of the old port (still just ‘port’ in 1850) until much later. That same mediaeval district was dynamited by the Germans during the war, then apparently rebuilt, and Marseille was one of the few southern cities to see a large number of deportations. The post-war period saw decades of colourful, semi-criminal mayors (a title destined for corruption), and horrific mismanagement of basic resources; though this has improved slightly in the last decade, the occasional building collapse still betrays its legacy. Defferre, the picturesque crook most emblematic of postwar Marseille, wanted a ‘shoot the boats’ policy for returning French settlers for Algeria; he was overruled and many of the now infamous slum housing estates were constructed to house them. The current holder is one of the tousle-haired white youths the various hard-left parties like sending to rule over their clients.

In terms of troubadours, Marseille was home to Folquet de Marseille, a merchant of Genoese extraction. Pound had a bizarre prejudice against the city, attacking it in something I read once, forgot, and cannot find again. It is probably the fault of the bishop-singer: Folquet spent most of his time in court at Aix writing cansos and eventually lost interest, packing his wife and family into holy orders, then joining Thoronet abbey, where he eventually became abbot. An ambitious man, he was later promoted to Bishop of Toulouse, where he had an extremely antagonistic relation with the city’s population and its count.

Folquet is one of the villains of the Chanson de la Croisade, the only troubadour in paradise for Dante, and disliked by Pound. He was probably not particularly active in the city itself, but Marseille hosted many troubadours as one of the possessions of the Baux family, and Peire Vidal was expelled from the city for stealing a kiss from its lord’s wife, an amusing anecdote that bears repeating:

Peire Vidal fell in love with all the fine ladies, and always believed they loved him back. He was in love with Lady Alazais, wife of Sir Barral lord of Marseille, who loved Peire Vidal more than any man for his skill in trobar and mad behaviour. Peire was admitted to the court and private chambers of Sir Barrall…

I will paraphrase to save us all time: Barral knew Peire was courting his wife and found it hilarious, as did the rest of the court. One of the recurring features of Peire’s biography is his total belief in his own charms – in his vida, ‘he thought all was made for his desire and pleasure’ – a view shared by none of his contemporaries, who nevertheless were in awe of his poetry and encouraged him greatly in his delusion. At Marseille, Peire honoured any woman who would listen in the court, and most pretended to go along with it.

One day, Peire found Sir Barral had left and his lady was alone in her rooms. Peire entered the room, and coming over to the bed found Lady Alazais sleeping. He knelt down, kissing her on the chin and mouth. She felt this, and thinking it was her husband, woke up laughing. Then she saw Peire Vidal, the madman.

This rapidly becomes a problem for our poet.

She began to scream and make noise, her maidservants rushing in from all over.

Peire flees, and Alazais demands his blood – her husband refuses, according to the razo acting like an honourable and just man he took everything as a joke, laughing and reproaching his wife for overreacting. But this was not good enough, and Alazais threatened our Peire so gravely he fled to Genoa in fear for his life.

In some accounts he then left for the third crusade with Richard Lionheart; after writing many poems attacking Alazais he eventually returns years later, once Barral had convinced his wife to forgive him. Then comes a comic ceremony where she ‘awards’ him the kiss he had once stolen. All this apparently happened after the Cyprus ‘Byzantine Emperor’ performance, since he berates Alazais for refusing the advances of the Emperor in more than one malcanso, or lovers’ reproach.

It is possible these songs had some role in Alazais accepting him back; Vidal was famous, and no matter his behaviour his adoration was an honour that reflected widely. His slander, with a sort of haughty self-pity I respect intensely, was of equal and opposite significance, Alazais surely keen to prevent it. But mostly he amused, he danced and gave pleasure, and life was surely more boring without him.

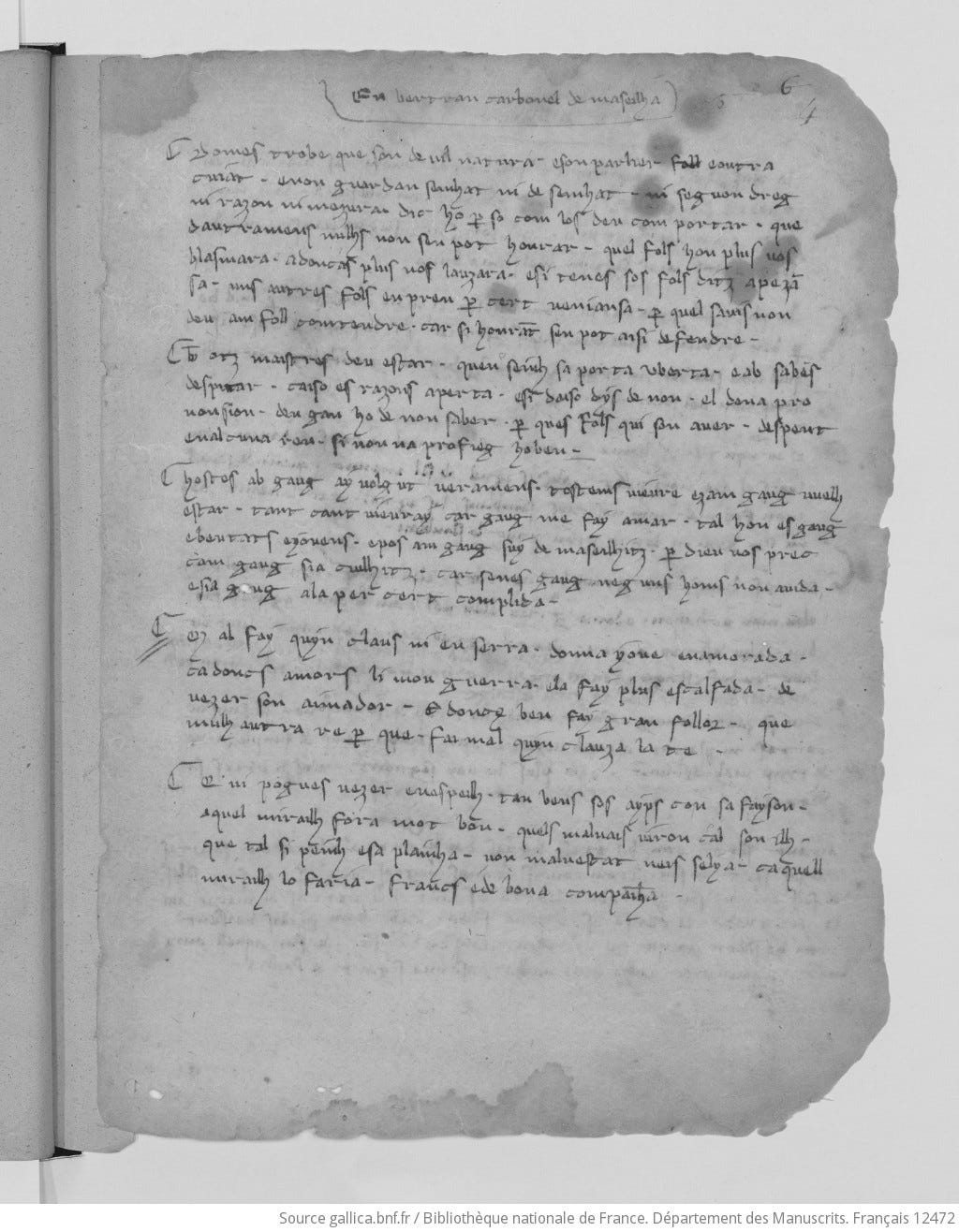

That bright and trivial world is gone, but Marseille still amuses. After the crusade – I made a solemn promise not to treat of decadents, and now will break it – the city became a haven for a moralising, Papist poet, Bertran Carbonel. He is preserved in the Chansonnier Giraud, a late and ugly document, the cansos unceremoniously copied out in a witches scrawl. In Nulhs hom non deu trop en la mort pensar, No man should think too much on death, Carbonel warns that dwelling on your own mortality will cause you to forget the joys of life.

Vidal, we can be quite sure, thought on it constantly, and only an exhausted age could produce such a warm-beer sentiment as Carbonel’s. His poems, short with a moral message, are quite easy to read, so useful for practice whatever their inadequacies.

As to Marseille: the city’s modern reputation is both just and unjust; poorer than her nearest equivalents, her name has become a byword for poverty in much the same way as Naples, but the picture is at least in part a false one. The immediate surroundings of St. Charles station give as misleading an impression as the Porte de La Chapelle does to Paris, but the recent history of the city is a fairly grim one of leftist machine control, gangsterism and slave labour.

Where Marseille compares favourably to say Birmingham is its setting: the climate is perfect for civilisation, seldom too hot or too cold, the mountains rise up from the sea more pleasingly than at Nice; there is a bizarre echo of Edinburgh, wilder, and another of Rotterdam. A constant wind rushing down the Rhone valley alternates with a softer breeze from the sea; the city is sunny enough that her concrete blocks are cheery rather than depressing, and steep hills protect against roaming zonards more effectively than in Paris or Lyon. Unlike Nice, there is never the sense of walking round an Italian occupied zone.

Such a large city seems out of place in Provence, where the essentially trivial nature of life is antithetical to vulgar striving or excitement, so as with Nice and Toulon the city feels like an imposition. Quite quickly heading into the suburbs, any pretence of metropolitan life ceases, the metro ending in blatant villages, or little stretches of beach down towards the Calanques, shielded from the old city by hills. It still vaguely looks like Marcel Pagnol country; GCSE French staple Jean de Florette was also set in the uplands around Marseille. But the town is modern, Corbusier’s Cité Radieuse full of sixty-something men in €300 ‘casual’ jumpers, the inside of the building a beehive of wood and coloured glass. The restaurants are fairly priced and you can drink coffee on the balconies, though the block is a pain to reach from the city centre, Marseille being the most spread-out city in France, and the one most geared around driving. I made do with a trotinette and swooped home along the beach. I spent too much time in Marseille to report on it anecdotally as with most of the stops on this part of my route; but she must surely be praised highly.

I am less sure of this point than I was in 2021/22; the city centre is a target for bobos fleeing Paris since Covid, and many of the suburbs (unusually for France, included in the official city limits), are stuffed with the descendants of Marius and the archetypal Marseille lady whose name I forget.

Marseille has a murder rate (7.5/100,000) comparable to Sacramento or Omaha; this is exceptional by Western European standards (the broader Bouches-du-Rhone department is at 4.1, France as a whole a little over 1) but very little of the city and none of the centre is objectively unsafe.