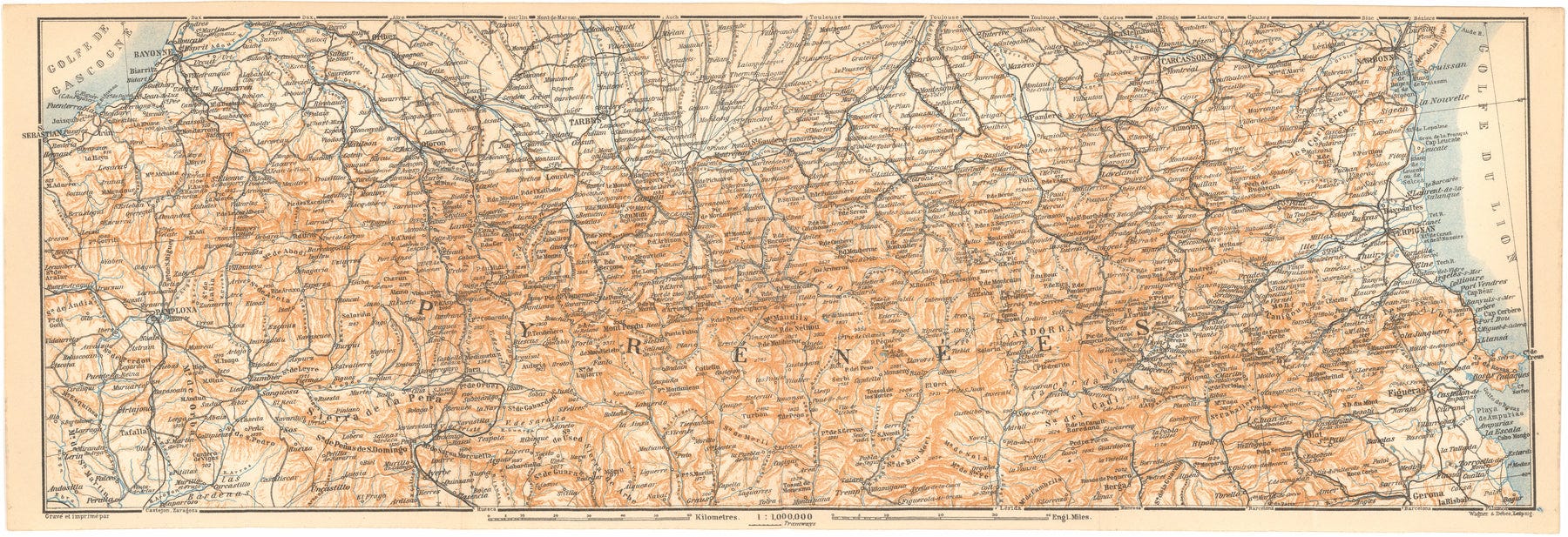

The BOOK, which, to my eternal shame, is gradually morphing into a far less honourable creature, a Blog, is arranged as a travel guide, something which is necessarily lost in the move to Substack. Ezra Pound started in Poitiers, covered the Limousin, then moved south across the mountainous fringe of Rodez and Cahors towards Toulouse, heading down to Foix by night before walking through a multi-day stretch of the Eastern Pyrenees.

Ez borrowed the classical pretensions of T E Hulme in London, and mountains were in poor taste for his social circle, they smacked of Ossianism, lacked the self-inflicted moderation that was (apparently) their first innovation. So he apologises in his notes for visiting them. I will make no such excuses, green vales and (decreasingly) icy cliffs all join my hymn.

The section below begins with one of the digressions or interludes which, in the book, provide filler material between the travelogue, arranged by region in the sense of Pound’s visit. The western part of Occitanie has just been covered, and Pound travels east through the Pyrenees, before arriving at the plain of the Languedoc at Carcassonne. Before this, and as Pound is taking his night-train south from Toulouse, we have an entracte, where I give you some things that don’t fit the narrative. Then we walk from Foix until the approach to Montségur, which merits its own section.

If you haven’t yet, subscribe immediately, then read:

Interlude

But in all this—the recollections of bitterness—& more especially of recent & more home desolation—which must accompany me through life—have preyed upon me here—and neither the music of the Shepherd—the crashing of the Avalanche—nor the torrent—the mountain—the Glacier—the Forest—nor the Cloud—have for one moment—lightened the weight upon my heart—nor enabled me to lose my own wretched identity in the majesty & the power and the Glory—around—above—& beneath me

Closing remarks of Byron’s Alpine Journal.

Byron wants something he can’t have; he would like to dissolve in the landscape, to lose his own wretched identity in majesty, power and glory –– that is, he wants to find an identity of majesty, power and glory ––– all things he presumably identifies with himself –– from standing on some rocks. The vulgar taste for ‘dramatic’ scenery is tied to this idea of dissolution: as with the sea, the setting is more appropriate for losing my own wretched identity the more fatal it is. Byron, of course, cannot accomplish this; his best work is only appreciated in France, he was a vain, vulgar man, and more entertaining for it. Compare:

The following situation may occasion this feeling in a still higher degree: Nature convulsed by a storm; the sky darkened by black threatening thunder-clouds; stupendous, naked, overhanging cliffs, completely shutting out the view; rushing, foaming torrents; absolute desert; the wail of the wind sweeping through the clefts of the rocks. Our dependence, our strife with hostile nature, our will broken in the conflict, now appears visibly before our eyes. Yet, so long as the personal pressure does not gain the upper hand, but we continue in æsthetic contemplation, the pure subject of knowing gazes unshaken and unconcerned through that strife of nature, through that picture of the broken will, and quietly comprehends the Ideas even of those objects which are threatening and terrible to the will. In this contrast lies the sense of the sublime.

Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation

Anyway, Byron doesn’t at all seek to be removed from himself into majesty, power and glory but to feel aware of them in himself, precisely by being on or near something which could swiftly remove any prospect of majesty, power or glory. For Byron the outside world is simply an extension of himself, so he never sees it this way, but trusts in an external force that he superstitiously calls nature. His desire is that of a drunk, he wants a passive force to take him outside of himself, to lighten the weight on his heart –– he is but personal pressure escaping itself.

The conceited, among whom I merrily count myself, often share this moment of frustration. Here it is expressed by Michelstaedter, though its result was opposite: I climbed a mountain – the altitude called me, I wanted it to be mine – I climbed – I dominated; but how to possess a mountain? I was above the plains and the sea; from the high peak I saw a vast horizon; but nothing of it was mine: that which I saw was not in me, and although my vision extended, I saw nothing. He gives up on mountains, and heads to the sea: though I swim through the waves, swallow salt-water, exult like the dolphin – even if I drown myself – I will never own the sea, I am alone and different in the midst of it. (Both Byron and Michelstaedter argued with their mothers.) The difference here is the Italian would like to identify with sublimity, rather than merely being distracted from himself in its presence.

This is a digression, but not an inane one: the impossibility of dissolving into something else is the frustration at the heart of most poetry. The amor de lonh trope emerges where love is impossible –– when a song to an achieved or achievable love is crass, not about love at all, love dies on completion – no-one wants to read the entrails of a Valentine’s card. As we have seen1, Guilhem IX, the first troubadour, sang of his conquests in the crudest possible terms, committing adultery on a massive scale and sending joglars to their husbands to brag. Later on, the troubadour starts to find this insufficient, and instead works out an idealised, impossible attraction, amor cortois. Notice that this does not lead Guilhem to reject his mistress, whose naked body was painted on the front of his shield. This idea, of a distant, withholding love that may or may not be requited, is enthusiastically taken up by the southern aristocracy, their instinct for love intrigue increasingly stymied by growing ecclesiastical power. Soon it becomes a cliché, and eventually, stripped of its original context, degenerates to a hypocritical form of politeness, and so enters France.

Jaufre Rudel was disappointed in his attempts with a certain Guillerina, penning part of a ludicrous debate poem over who was more honoured by her looks (which went everywhere), hand presses, and so on. Courtly love in the vein of the first troubadour wasn’t working for him, so Jaufre redirects his search to the absent countess of Tripoli. I do not believe the vidas are fictions, though they certainly include errors, and wonder if his death stemmed from a vulgar quest to realise his love by leaving for Tripoli. Certainly it is possible to see the dying in his lady’s arms as the death of love on consummation. On the face of it Peire Vidal is lo plus fols hom del mon, but I prefer to think he understood this problem, and so kept shifting his target to ever more inappropriate ladies precisely to keep this tension alive, and his verse productive. Tellingly, Vidal’s death and final years are unknown, we just lose the thread somewhere, he disappears, dissolves into the background, he walks off into a forest. Vidal, it is old Vidal speaking, stumbling along in the wood…

Byron senses this, but cannot explain it outside of prose letters; like the lover who attains his object, walking on and being in the presence of something simply reminds him of the unbridgeable distance, most horrifying of all: between two things sat next to each other. He and his contemporaries polluted the mountain air to the point where Old Ez had to apologise for walking through the Pyrenees, something no known troubadour would’ve shared the urge for. Mountains were already decadent in 1912, partly the fault of Uncle Byron’s excursion. Nature more generally is something to be wary of for Ez, eager to distance himself from Daffodils; to be as mad as the shepherd who plays his pipes to a beautiful mountain is never his aim. It should be pointed out, as Pound does, the eastern Pyrenees have a pleasingly (forgive me) Oriental quality to them, and none of the aggressive vulgarity of the Alps: the Alps are, even by the standards of mountain ranges, ugly. But we have drifted away from relevance now, and so go back to the road.

Part three: Occitanie (Pyrenees)

Some mountains in France, that are on this side of France; this is why we have digressed about mountains in the last pages. Ez says that to goon on pilgrimages is an ancient and respectable habit, but considers visiting mere mountains decadent. We shall now see if he was right.

Foix

We are come again to a place where the waters run swiftly and there is always this Chinese backdrop

Ez, 1912

At Foix, Ez –– a barely-suppressed Romantic – starts talking about China and mentions it non-stop until Quillan. It’s curious that someone born in the Rocky Mountains should think of China at every hill, but at times he is right, especially on the road from Montségur to Puivert. I don’t know if he said the same at Garda. Ez is no chaser of scenery, and I suspect he would have approved the Chinese custom of writing poems of appreciation on blank stretches of landscape scrolls. Framed ‘art’ pictures were of little interest to Ez, a fresco and altarpiece man by justifiable preference. We are rambling, even if the first man who compared poetry with painting was a man of fine feeling, so back to Foix. An ungovernable mountain principality, several of Foix’s counts took to trobar, some were close to heretics. And Ez quotes a stanza from a late anti-French piece dating to the 1280s war between France and Aragon:

Mas qui a flor si vol mesclar,

Ben deu gardar lo sieu baston

Car frances sabon grans colps dar

Et albirar ab lor bordon

E nous fizes in carcasses

Ni en genes ni en gascon

Which Ez translates:

Let no man lounge amid flowers

Without a stout club of some kind,

Know ye the French are stiff in stour

And sing not all they have in mind,

So trust ye not in Carcason,

In Genovese, nor in Gascon

And Linda Paterson gives as:

But anyone who wants to mix (or do battle) with flowers should guard his rod, as the French know how to give mighty blows and aim straight with their lance; don’t rely on the Carcassès or the Agenais or a Gascon.

The flowers probably refer to the fleur de lis on French arms. The Aragonese ‘Crusade’ was an ill-fated attack by the French with papal backing against the Catalan belt and what remained of independent Occitan territory, continuing a feud started in the Sicilian Vespers. Philip III would die in Perpignan in the aftermath, but it is interesting Foix reports disappointment in his allies of 60 years ago, also once main patronage courts of the troubadours. At the time of the crusade Esclarmonde of Foix was the count’s sister, and a famous parfait; her memory important to various socks and sandals cults that sprung up once the usual suspects found out about her, there are bad neo-Occitan poems and so on. But as Ez reminds us, to goon on pilgrimages is an ancient and respectable habit, so we forgive them their masturbation.

The count of Foix, Raymond-Roger, was linked romantically to the Loba Peire Vidal sang to in Carcassonne; he was also responsible for an early victory against the French in 1211, when he destroyed a group of German and Frisian crusaders some miles north of Carcassonne. Peire d’Auvergne was here, who called his poems vers instead of cansos. Raymond-Roger of Foix, effectively independent in his scrubby territory, was one of the main résistants during the crusade, and a later count, Gaston Febus, wrote what is probably the best known Occitan song, Se Canto. Febus, named for Phoebus Apollo, is also notable for crushing a peasant uprising against the French nobility in Oise; the royals quite happy to employ the family when it suited them.

The counts of Foix had a well-earned reputation for violence; in 1212 the Count massacred a group of monks and pilgrims, and despite failed punishment expeditions, de Montfort could never successfully rein him in. Despite this, their territory was too poor and disorganised to be decisive in any of the campaigns they were involved in. When de Montfort died Foix raided Arnaut Amaury’s new lands around Carcassonne, leading away a great herd of stolen cows into the mountains – ultimately he represents a type whose time had not yet come; it is quite easy to see him in Urbino or Rimini, but despite poetic enthusiasms and a taste for heretical learning, he lacked the full kultur of Federico Montefeltro, or Sigismondo Malatesta, his lands too poor to sustain a great patron. Ez is enthusiastic about Foix, I dislike the city, it is a camper-van place, the wrong kind of hippy, they vote for Mélenchon and look dirty. La ville la plus ringarde de France. Night sets in early behind the mountains and the centre is often squalid. Ez arrived by night train from Toulouse, a route which now takes around an hour, so his train must have proceeded at a crawl.

Leaving Foix on the D9 towards Roquefixade, the city is more attractive once behind you. After crossing the mildly frightening river, the town is reduced to a castle on a hill ringed with some houses. These rivers, with their supernatural blue colour and murderous currents, lurk at the bottom of disproportionate beds, waiting to jump out and drown people in Spring. Foix’s mountain, which Ez claimed looked like an elephant, is a glorified hill, the chateau lit up pink by night. The D9 clears the city quickly as you approach another lump of grey, the pain du sucre, before climbing through woods on the approach to Roquefixade, after an enormous rib of rock. I passed a car smashed to pieces on the side of the road, 15km in vicious cold. You can buy a house for next to nothing in Foix – don’t. The city is also clouded for me by the presence of someone I really should have let know I was visiting, but didn’t, so perhaps do not trust my judgement either. You must see for yourself, sometimes.

Roquefixade

The next village on the way to Montségur, Roquefixade is a desolate place with a covered square and church porch piled with farm equipment. Its chateau is perched in a breach along a long rib of rock; Ez considered himself wildly courageous to have climbed there, the maddest and one of the sanest things I have ever done - etc etc – but there is a footpath: this is in no way equal to the Coleridge Broad Stand anecdote I shared above. Ez tells us about this place there is nothing in the archives before listing the dimensions of the keep, and walking on. I was chased by a rottweiler on entering the village and didn’t bother climbing to the castle, the village closed to nothingness, with the scrappy air mountain places always have.

The valley leading to Lavelanet is a bleak and cold one. Here my route briefly separates from Ez’s; at the intersection of two valleys he pushed into the centre of Lavelanet, where he stayed for the night, and I continued round to Montségur. There is an obscure reference in his notes –– descending Roquefixade by the other side ––– to my understanding it is not possible to reach Lavelanet this way –– I wonder if he ascended on the far side of the rib and climbed back down through the village. This is trivia and ghost hunting, without relevance to litterachur, so we will continue.

Some words on Roquefixade, before we leave. Apparently, the village was founded as a bastide, a royal fortified town at the foot of the castle, and originally named in honour of Simon de Montfort. Roquefixade has lost 75% of its population since the mid-19ᵗʰ century and is moribund, with 150 or so people left, but fairly picturesque in its ruin. The castle probably had something to do with the crusade given the village’s foundation and old name, but no-one can remember what it is. It is important to remember how imprecise the location of mediaeval battles really is –– it’s not inconceivable this was Montségur. Regardless, there was nowhere I could find to buy supplies, which in the argot of those places six thousand feet beyond man and time signifies groceries. So, with no reason to stop there other than the castle, I walked on to Montségur.

Great read I'm more familiar with the higher Pyrenees. Chateaubriand was a fan of the same region! Tennyson also spent some time in the Pyrenees supporting the Torrijos revolt!

https://stacdavey.substack.com/p/the-pyrenees-2-desolation?r=lbqkv