Gironde: Old Ez and the Trobar (III)

Aftermath - Tuscans and Italians - The troubadours in Pound's milieu - Why 'Gironde' - Pound's historical method - Provencal and English verse - Whose idea was it

We are continuing from the last two updates - in Part One we found out who the troubadours were and why Pound cared about them, while Part Two explained their condition and historical position. Below is the end of the beginning of our introduction, and is mostly about the troubadours’ reception, influence on English poetry, and why Ezra Pound set off walking after them in the summer of 1912. The subsequent posts will deal with my trip, how I worked out and followed Pound’s route, and briefly start talking about the places themselves.

I have said:

‘Here such a one walked.

‘Here Coeur-de-Lion was slain.

'Here was good singing.

'Here one man hastened his step.

'Here one lay panting.'

Ez, Provincia Deserta

Tuscany, Italian troubadours, and recorded music

Like everything, it fizzles out eventually; outside of Toulouse and after the demise of the trouvères, the troubadours are largely forgotten as France begins to have a non-parochial literature of its own, and it is in Italy where the memory of their songs is best preserved. There is a direct link between the later figures and Petrarch, who visited Toulouse and lived in Avignon for years at a time, possessing at least some knowledge of Provençal, while Dante was in Arles during the decadent period. The presence of troubadours at courts in both northern Italy and Sicily boosted the Italian prestige of vernacular literature, and Dante has troubadours in Hell (Bertran de Born), Purgatory (Arnaut Daniels – prompting Dante’s own composition in Provençal) and Heaven (Folquet de Marseille – to Pound’s chagrin). There are others too but I’ve forgotten them; this is trivia, you can look it up yourself. Many originally Provençal forms gradually came to be seen as Italian, especially in England where Chaucer’s ‘French’ and ‘Italian’ periods can both be directly traced to Provence – a point raised by Pound, and repeated by yours truly. Like many of their admirers, Pound discovered the troubadours through Dante, and places a heavy emphasis on names mentioned in the Comedy; one of the anthologies he used as a student was Henry Chaytor’s Dante’s Troubadours.

Tuscany probably played the biggest part in preservation of the living tradition, while Venice was the source of many 13ᵗʰ century manuscripts, but their legacy was not just Italian. In Provence, the old seer Nostradamus’ brother worked as an anthologist, boosting their prestige but often fabricating biographies and misreading place names to move the action of the vidas to Provence proper. Admirers trickled in over the following centuries; Barbieri in the 16th, one of the occasional antiquarians preserving them alongside the trouvères, a song by Folquet de Marseille transcribed alone under the heading ‘a few Provençal songs set to music’.

For many years troubadours remained a fringe interest for musicians, but the texts and melodies gradually started to be ‘collected’ and praised by various luminaries, up to and including Rousseau, so that by the year 1800 century warm noises from Schelling etc. announced their return as an important thing in European letters, a status which lasted until the mid 20ᵗʰ century. Eagerly leapt upon by the usual magpies, paintings soon appeared in style troubadour, a gimmick copied a few decades later by the pre-Raphaelites. All of this worked to seal the troubadours’ gradual, mildly dishonest insertion into the canon of ‘French’ letters, a north-European spirit to which they are fundamentally opposed.

The Troubadours in Ez’s day

By the late Victorian period the troubadours were immensely well-reg-h’arded; in Pound’s youth they reached the peak of their popularity. These few hundred poets became the favoured target for German philologists running out of meaningful remarks on the classics, and proved significantly less boring than the 200,000 line nursery-rhymed allegories that make up mediaeval fare elsewhere (this also exists in Occitan but is less well-preserved). By the dawn of the 20ᵗʰ century they were popular enough for glossy mass-market books with photos, a subject for travel guides, such as the two-volume The Troubadours at Home (hereon TTAH) by Justin Smith, an American historian.

This book is very important, a travelogue detailing his trip through the troubadour heartland, and became the basis for Pound’s 1912 voyage. Although he inverts its sense, he follows Smith quite faithfully, using the Baedeker guidebook series to supplement and plan routes. TTAH is a work of imagination, based somewhat faithfully on the vidas and information in songs, with long digressions on ‘the mediaeval mind’ and other such things; mostly it is a straightforward, breathless account of a trip through the south by the sort of man who gets excited by florists’ displays and thinks coloured shutters are echt. By all accounts, the book was a significant financial success (it is easy and cheap to find copies today, no mean feat for an expensively bound book with inserts), and since Pound’s was never published I have used both freely for source material.

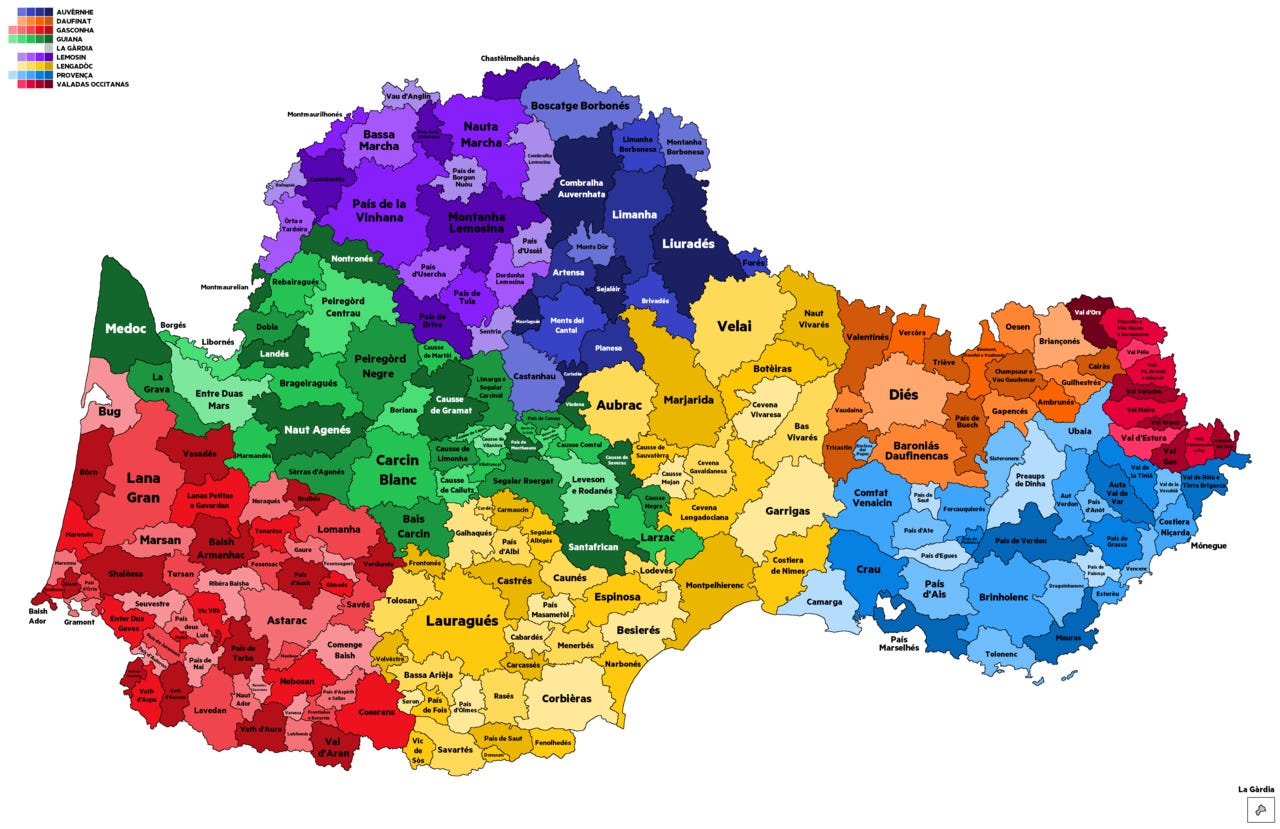

Gironde and Occitania

Pound called his book Gironde, after the estuary near Bordeaux where the rivers Dordogne and Garonne meet. The Dordogne drains the first part of this guide, while the Garonne, which starts in a glacier on top of the Spanish Pyrenees, accounts for most of the rest. This hydrographic symbolism may well be an accident, but is made more interesting by the fact the estuary drains into the Atlantic rather than the Mediterranean. This waterway accounted for most British trade during the Middle Ages; the western side of southern France was an integral part of the Plantagenet kingdom. What came to England from France in the middle ages normally came through Bordeaux, the largest Plantagenet port and likely second city by population after London, although this is to some extent guesswork; there were around 20,000 souls in 1300, and probably not much less in 1200.

A large number of ‘French’ etymologies in English are in fact Occitan; colander and noose are only ones I can remember, but they all came through here, as most likely did Bertran de Ventadourn, when he moved to England following his patron, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Since Ez never visited Gironde in 1912, the name is likely symbolic, Pound’s intention (I assume) to write an opinionated version of TTAH where he would put forth his own literary theories on the troubadour art and the poems’ composition.

He had a reasonable hope for the book to sell: translated troubadour anthologies did well, a few of the most famous names were genuinely well-known, and the poems were popular; ornate prescriptive styles easier to swallow back then, (largely misrepresented) theories of love exciting but palatable for shut-in women, Protestants able to play ancestors with the persecuted victims of the crusade, philologists building careers ‘adding blocks to pyramids’, listing vowel changes and slow mutations. Pound delivered a series of lectures at Regent Street Polytechnic on exactly this subject, later collated in Psychology and Troubadours. These probably weren’t very well attended, but still show a general interest quite absent in recent decades, in England at least.

Both academically and popularly the troubadours were a big deal and the young Pound’s interest is unsurprising for a poet of his generation: it is curious that (in the Anglophone world at least) interest collapsed after him. After the initial antiquarian excitement of the 18th and 19th centuries, much of the later French focus on the troubadours, up to Michel Zink and others writing today, uses a forced anti-colonial reading of Occitan history. All-pervasive in the later 20ᵗʰ century, it is apparent in the work of René Nelli, who still produced a number of good themed anthologies and social histories of the crusade. Since concepts like Latinity and la Méditerranée had been tainted by association with Action Française and Vichy, and with a complex internal politics that saw pro-Communist Occitanists (such as Nelli) prosper post-war, later revivalists went out of their way to stress left-wing credentials and a syrupy performed ‘folk culture’.

The school-age introductory textbook to modern Languedocien takes pains to remind readers that Occitan is not an ethnicity. This became one way of washing the older defence of a distinct, racially defined southern France, like Mistral advocated. I think we can safely assume Pound would not have appreciated Occitanism; he dies just as this school is starting to flourish and his virtual silence from that period forbids us to guess.

So Pound met the troubadours as an undergraduate, introduced to them by Dante, like a great many of their conquests. He immediately decided they were of importance to his project – technical renewal with a prejudice for the earliest root examples of English poetry – and set off.

Pound’s method: why a walking tour?

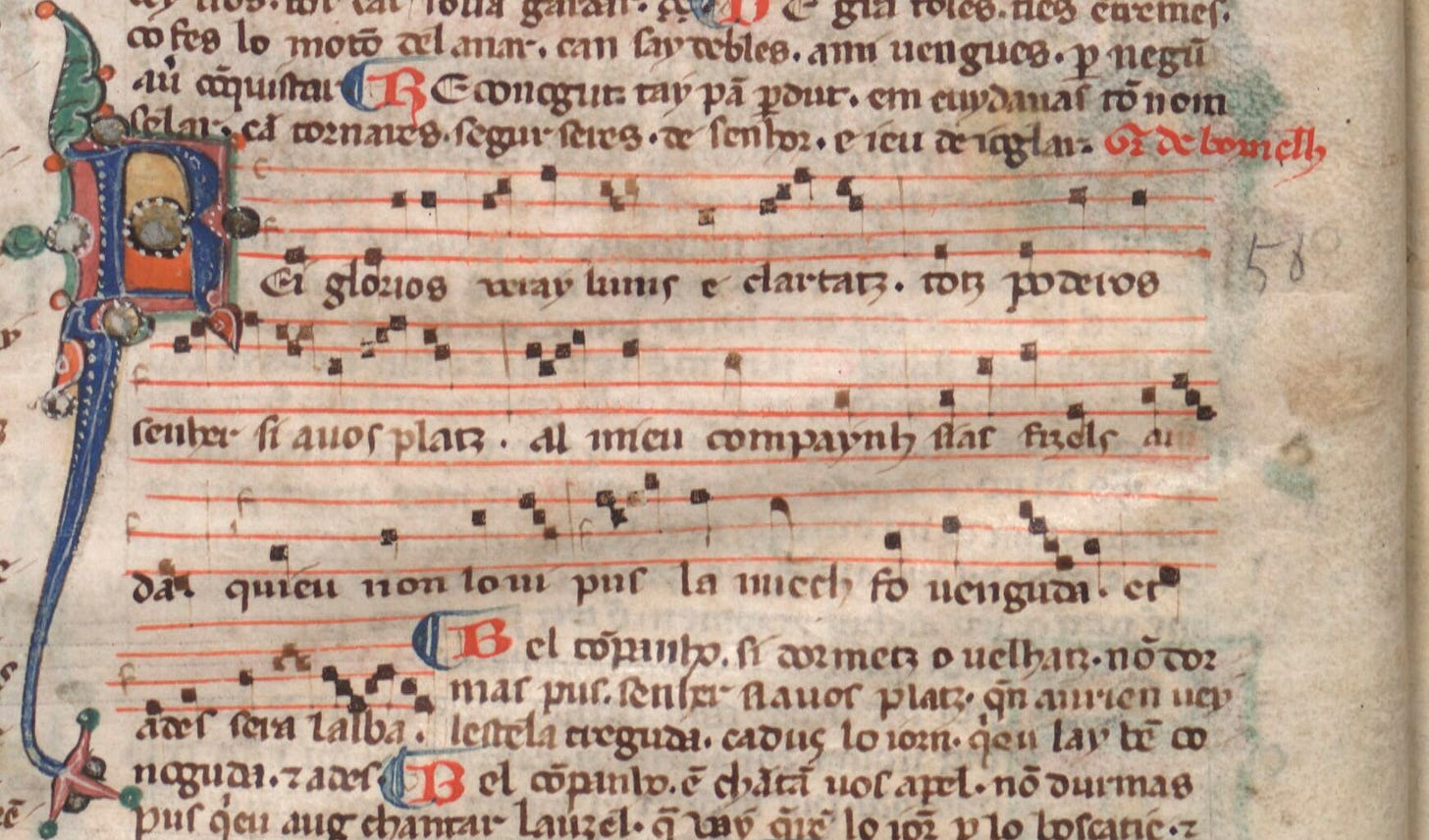

In Psychology and Troubadours, Pound offers three methods for understanding their verse. The first was studying the illuminated vellum chansonniers, to see their reception in the following century (most date 1250-1350; Pound used the Chansonnier La Vallière, and another in Milan). Second, he worked directly with the surviving melodies, transcribing and performing adapted songs with Walter Rummel, using tunes copied from the above manuscripts.

Finally, and giving rise to the walking tour, he physically followed the same roads the troubadours used, faring from court to court across Provence. Pound truly believed in the efficacy of this method, and in addition to greater familiarity with the condition of the troubadours, it gave him a wealth of material used in short poems and the Cantos. Pound wasn’t above ignoring drastic changes to the landscape and social structure of the region; he is inside his head for most of the voyage, unlike your witty and perceptive correspondent.

In the first two of Pound’s methods I have no special advantage; the music is far more widely available now than it was in 1912, and you can easily listen to high-quality versions of many surviving songs or find scores for piano; the manuscripts are digitised and available online in high resolution, unfortunately only in black and white in some cases. But aside from an ephemeral online map by Eloisa Bressan, if anyone has spent as much time recreating his walking route as I have they have not written about it; Richard Sieburth drove it, the interactive map was hosted on an academic website for a while, blurry screenshots all that remains. So goes the ‘digital humanities’.

A genealogy of poetry

Back to Pound: his concern, perhaps not explicitly in 1912 but already in an embryonic fashion, was the renewal of all European and ultimately all world poetry; his first two studies are college-based ones into Old English and Provençal. Unlike Auden and later British poets, Pound loses interest in Old English early on; his adaptations of Anglo-Saxon mostly limited to Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Reader (I briefly struggled with and then wisely abandoned Sweet’s easier Primer), as in his famous version of the Seafarer or the first Canto, but the twee groupuscules around Tolkien and Auden would never have appealed to ‘Mistah Pound, who likes foreign languages’, so Provençal and Italian end up doing most of the lifting in his system. Ez’s insistence on using canzoni to refer to Provençal cansos is just one example of his Italianising; various intricate theories of platonic love are also either late or absent in Provençal; he reads them in via Italy. Ezra Pound may have been a neo-Platonist, but the troubadours were not.

On the technical side, Pound’s system goes as follows: Anglo-Saxon alliterative verse + Provençal rhymed lyric, repeatedly subjected to classicising influence over subsequent centuries = English verse. This is correct: there is no continuity between classical antiquity and modern English, but a continual development from scraps of surviving Anglo-Saxon, radically changed by the growing prevalence of French and Italian forms, an influence which starts early, but arrives at full fruition in the 14ᵗʰ century and is borrowed ultimately from Provençal. Since all literature is translation, his work must be, and Pound makes his intent obvious early on.

His model, TTAH, provides banal translations and interpretations for a large number of poems, rhymed in then-fashionable patterns; these are old meringues, crusts to be avoided. The error, probably forgivable at the time, was to impersonate troubadour rhyme schemes rather than the sense of the words, and copy them formulaically rather than fishing for an English equivalent, or simply providing lined prose. Pound changes the meaning of poems as he translates them; I don’t see anything particularly wrong with this. It is right to use any ‘translated’ poem as an excuse to sneak in your own. The sound of the poem (I will not use Pound’s silly jargon) can never be translated; sense without it, particularly in a piece of music, is a relative concept.

Pound abandoned his studies, and was never interested in producing a critical edition. Though he may have fooled himself he was translating faithfully, his intention is largely irrelevant. Once a poem can no longer be put to good use it should be lost, the final manuscripts destroyed, the work of repeating them falls more on loyal falsifiers than on philologists. It is quite appropriate for a poet to survive only in quotation; much of the artifice falls away, and only the odd phrase, which is accidental – and so telling – remains. Meanings obviously drift. When Bernart de Bondeills, preserved in a single song Tot aissi·m pren com fai als assesis, compares himself to an assassin, he is referring to their loyalty, not their capacity for murder. 1912 is an inflection point where his previous focus; accurate translations of romance texts, reproducing their forms in English, gives way to a broader type of semi-original poem, derived only loosely from a historical source. These cover nearly the full range of Romance languages alongside Anglo-Saxon and Chinese, and make up a large part of his subsequent short verse and Cantos.

You will notice I have offered translations; in principle I am against facing translations, books for language learners are best when they have an appendix in English or a crib of certain words, ‘artistic’ translations suffer from being put beside the original. Having both on facing pages will always either result in one being used as a bad glossary or the other simply wasting ink. I feel this very strongly and have ignored it below; let your judgement not be too heavy upon me.

The movement of English verse, from accentual lines split into two halves and punctuated with alliteration, to syllabic rhymed verse vaguely recognisable as ‘poems’, took place because of changes in the language following contact with Romance languages. In all honesty, rhymed Latin verse was likely much more important than anything in this book, but Pound’s unfailing instincts rightly tell him this is boring and so we find ourselves in Provence. I am aware I’m stating this without providing any real proof; Big Ezra said it, it intuitively makes sense, but I want to stress the root importance of Provencal so that we do not fall into thinking this is a foreign trip.

Influences on the troubadours

The various continental influences grafted into English poetry and re-accessed directly by Pound (Anglo-Norman, rhymed Latin verse) are themselves heavily influenced by the troubadours, and as far north as Germany explicit references to troubadour poems exist in the Minnesingers. Mediaeval Latin highly relevant as one of the major influences on the troubadours; very likely they fed into each other, I suspect some of the more clerical poets wrote both. This is a travel guide though, so we are not obliged to torture ourselves with such questions. As for England, Bernard Ventadourn went there in person; Richard I wrote his own cansos, this is at a time when domestic poetry was still full of:

Merie sungen ðe muneches binnen Ely

ða Cnut ching reu ðer by.

Roweþ cnites noer the lant

and here we þes muneches sæng.

Merrily sang the monks from Ely

The King Cnut rowed there by.

Row, knights, nearer the land

And hear we the monk’s song.

And so on. The problem with Pound’s theory, even the exaggerated version I’m pretending is his, is what exactly þes muneches sæng – here is also perhaps a credible answer to the ‘where do cansos come from’ question, and one that exonerates the southern neighbour in both cases. From a very early date there are denunciations of lay priests for singing scurrilous or sacrilegious songs, possibly with a role in carnival celebrations at universities. Due to their knowledge of Latin they were protected from civil action, a privilege that local bishops threatened at times to revoke. Possibly Marcabru and definitely the Monk of Montaudon had a clerical education, Goliards in the vernacular; it is worth speculating on any potential Latin works, but this can never be proved. Whatever their relation, the troubadours and Goliards are the earliest preserved secular musicians in Europe (at least in a continuous, non-fragmentary tradition), and their musical education was certainly based on that of the Church. A link to liturgical music of the Abbey of St. Martial at Limoges (now underneath a car park) is sometimes mentioned; Poitiers and the region of the first troubadours was either within or next to the diocese and their influence would have been extensive. Both sacred and secular music were somewhat open to embellishment, the neumes offering a less-than-exact guide to pitch, and none whatsoever on rhythm, so pieces varied from performance to performance, as they still do today.

Less vague than the preserved music are the prose apparatus around the songs. The vidas (brief prose introductions or explanations), were later works by scribes, but razos (explanations of the song) were part of the performance. Though the surviving razos are written down some time after the high period, descriptions exist of troubadours singing and then explaining, often with multiple conflicting versions, their own and others’ songs. Taken to an extreme degree, this ends up sounding a little too close to the lesser sort of poetry reading to be taken entirely at face value: Richard de Berbezill ‘knowing better how to compose than to understand or explain’ could just as easily be ‘… than to listen or speak’, and the next sentence mout fo pauro disenz entre las genz is surely referring to conversation in general rather than ‘explaining’ his songs. Such quotes have led dull people with Derridean pretensions to claim the songs were riddles, guessing an interpretation part of the ‘fun’, a common theme in articles and books on the troubadours from c1990-2010. Away from this nonsense, troubadour audiences expected close conformity to existing rules, or deviations with sense. There exists from the beginning defined genres and schools, formalised in prose treatises as early as 1200-1215, who offered prescripts most singers conformed to, each song original but only within strict limits.

While I could believe Goliards played that kind of academic game, perhaps even with troubadour songs they were exposed to, it is not credible to imagine Bertran de Born ironic. As the decadence set in, composition guides multiplied, and the topics of song became more stereotypical, so that sort of intellectualising performance became more and more necessary. It is also probable they were more common outside of the Occitan-speaking region. On the whole, songs were sung simply and directly, and contemporary performed versions tend towards the popular, influenced by some of the same currents as the rest of the ‘Occitan revival’. This has led to claims the troubadours formalised an existing, popular tradition. For some genres, notably the pastorela and possibly the alba, this may be true, but deciding either way is unnecessary. Ez:

I see every reason for studying Provençal verse (a little of it, say thirty or fifty poems) from Guillaume de Poitiers, Bertrand de Born and Sordello. Guido and Dante in Italy, Villon and Chaucer in France and England, had their root in Provence : their art, their artistry, and a good deal of their thought.

Pound focuses on a few personal favourites and uses them as types for vast categories; he borrows these favourites if the work to approach them is significant enough (especially from Dante). This is a source of much annoyance with Pound, but is really a strength, the Cantos impossible without it. It is also a reasonable strategy for reading them. For Pound, The Odyssey and Sappho are Greek, Ovid and Catullus Latin, the few troubadours mentioned above Provençal, and Dante / Cavalcanti Italian. His focus, guided by accidents, allows him to cover vast territory of time and space.

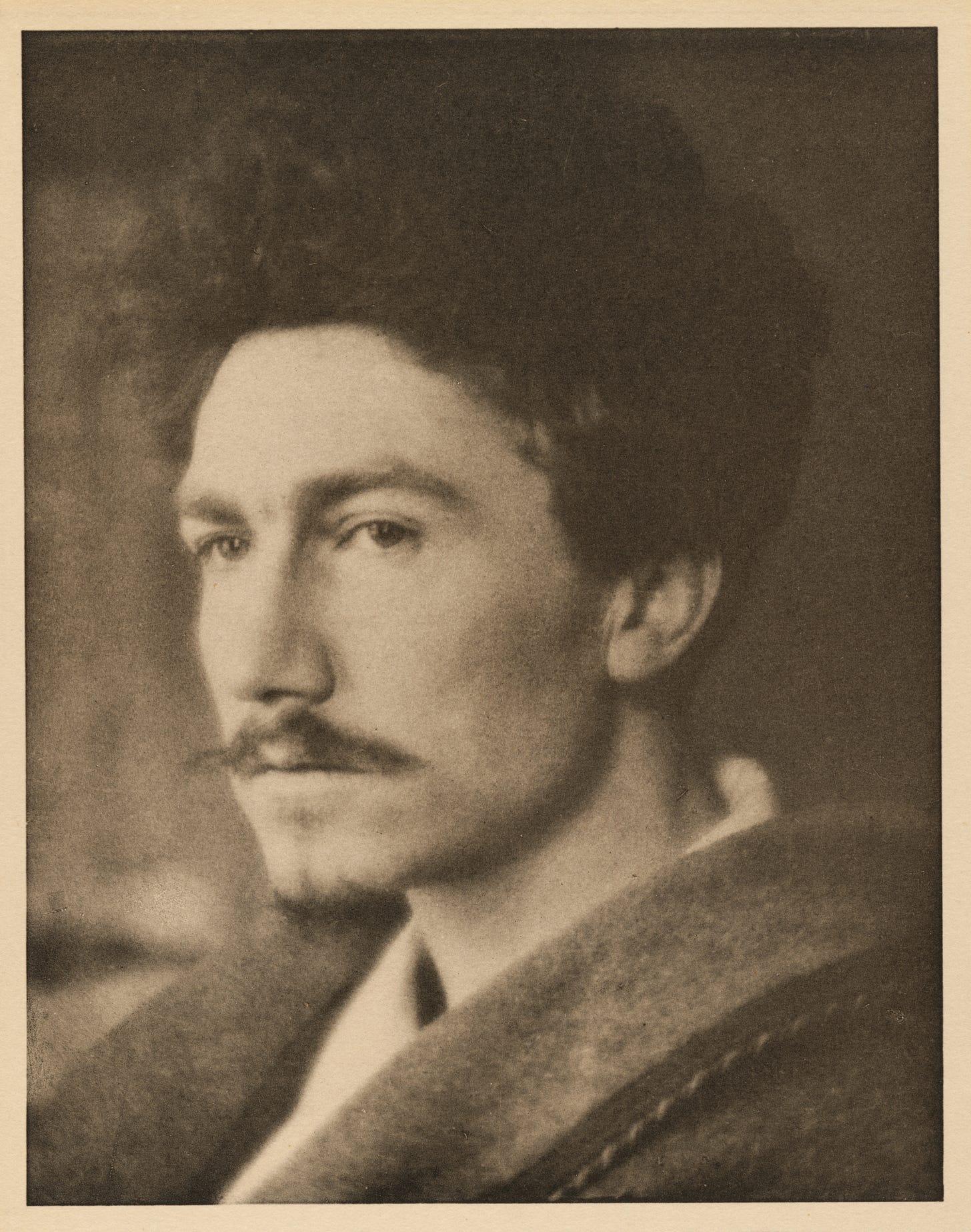

Old Ez and his poems in 1912

In April 1912 Pound was a marginal figure, the alleged success of ‘imagism’ yet to materialise, and surely exaggerated by its participants in later years. At the time, his own verse was in direct contradiction to his critical opinions, with dense flourishes ever-present in early collections and intermittent until much later. These early poems were accepted and encouraged by institutional poetry, especially in the USA. As soon as his mature style appears, they reject him, and he is reduced to friends’ magazines. It is also worth pointing out Pound’s reputation has always been more as ‘a poet’ than for any of his poems individually, and this was deliberate; it is far rarer to meet someone who has memorised anything by Pound (I am not including the tiny one about the metro station) than Eliot or lesser-known contemporaries. Fame hangs off the name far longer than the work.

Away from his abstracted reputation, Pound is always preferred by those heavily involved with poetry themselves, reinforcing the split between his reputation and popularity as a poet. Prose-wise he is best when writing on verse or laying out his method, his political broadcasts alternate rhetorical bombast in dialect – the breedin’ of human beings deserves MORE care and attention than the breedin’ of horses or wiffetts… that means EUGENICS as opposed to race-suicide’ – with a plodding commitment to ’heconomics. I’m not surprised Gironde was binned: there is no literary genre that can ‘contain a travel guide’; this is a popular and low district and in fact TTAH understood better how the poems needed to be mangled to produce something that could even half claim to ‘work’. TTAH avoids including Provençal text, translates all poems florally, and styles itself as a work of the imagination. Pound I imagine was unwilling to do the same, and suffered the consequence.

I have wandered around – where are we now? 1912 is mostly obscure, 1200 no longer exists, to copy a derivative work is to repeat an error, only to do so in a more ignorant and less interesting fashion. Were I a few years further into the worst generation I would try and make a joke out of this; layer the travel guide in notes with boring conceits, write in a silly voice, take seriously ‘Rosicrucianism’, and so on. Cowardly, as is simply identifying the criticism and leaving it, but at least this way is easier: it would not even have occurred to Pound. Tranquille.

To be continued…